420 years after its first performance, Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus returns to The Rose Playhouse, Bankside. In this version the original text has been cut down to an 80-minute one-man piece. It’s a bold move that unfortunately doesn’t pay off.

At the core of what has made Doctor Faustus a universal play and often quoted literary motive for well over 400 years, is man’s fascination of reaching beyond what is known and what he is ready to sacrifice for that. It’s nothing less than the progress of society that depends on the very urge to move the boundaries of knowledge forward. A new approach to a classic text, which gives us a different angle on the brooding Faustian hero is therefore always welcome. The fabric of the narrative is well known: German scholar Faust dons the robes of common scholarly disciplines and shrouds himself into the dangerous cloak of dark magic.

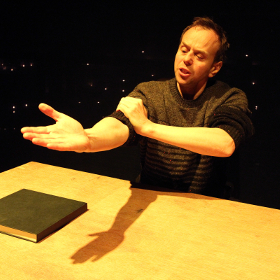

An empty chamber, a chair and a desk with four books – it’s a plain setting for the infamous pact with the devil, which turns out to be a disappointingly anaemic affair.

Christopher Staines gives a committed performance as Faustus but he does not quite create the necessary magic pull to hold the audience’s attention for the entirety of the piece. It all hangs together somehow but only by a thread, and instead of going from soaring height to height, the piece moves somewhat sluggishly from well-known quotes and even better known soliloquies. Devils, dragons, magic tricks – that’s what Marlowe’s existentialist romp is known for. If the spectacular is removed from the piece it should be replaced by something very substantial and fundamental. It hasn’t been, and that’s the crux; and it so happens that the audience arrives at the famous Helen of Troy speech without really having made the emotional journey to appreciate the melancholic yearning of a man filled with regret who is yet unable to repent.

A stark deviation from the original text set in the Vatican shakes the whole piece up a bit. In an improvisation sequence Staines degenerates into a childlike state and speaks in funny voices with little torn-out-bible-pages paper men. The sight of a man who was out to examine the fabric of space, human nature and knowledge and ends up mistaking practical jokes for power needs to be more tragic than what’s offered here by Staines and Parr.

Or is the actor in the end just a mad man in a cell? Is the voice of the devilish henchman Mephistopheles just in his head? If this was a proposed reading the directorial pushes were maybe too weak to create a gripping conceptual angle. It’s stripped too bare to be visually engaging; even the setting of the Rose excavation site in the background dotted with hundreds of candles doesn’t change that.

While his last year’s Hamlet was a bravely cut version that zipped along rather nicely, this new offering from director Martin Parr lacks a distinct narrative purpose. One can’t help but think that the commemoration of Marlowe’s 450th birthday would have deserved a more captivating version.

Please note: The reviewer saw the preview on the day before the show opened.